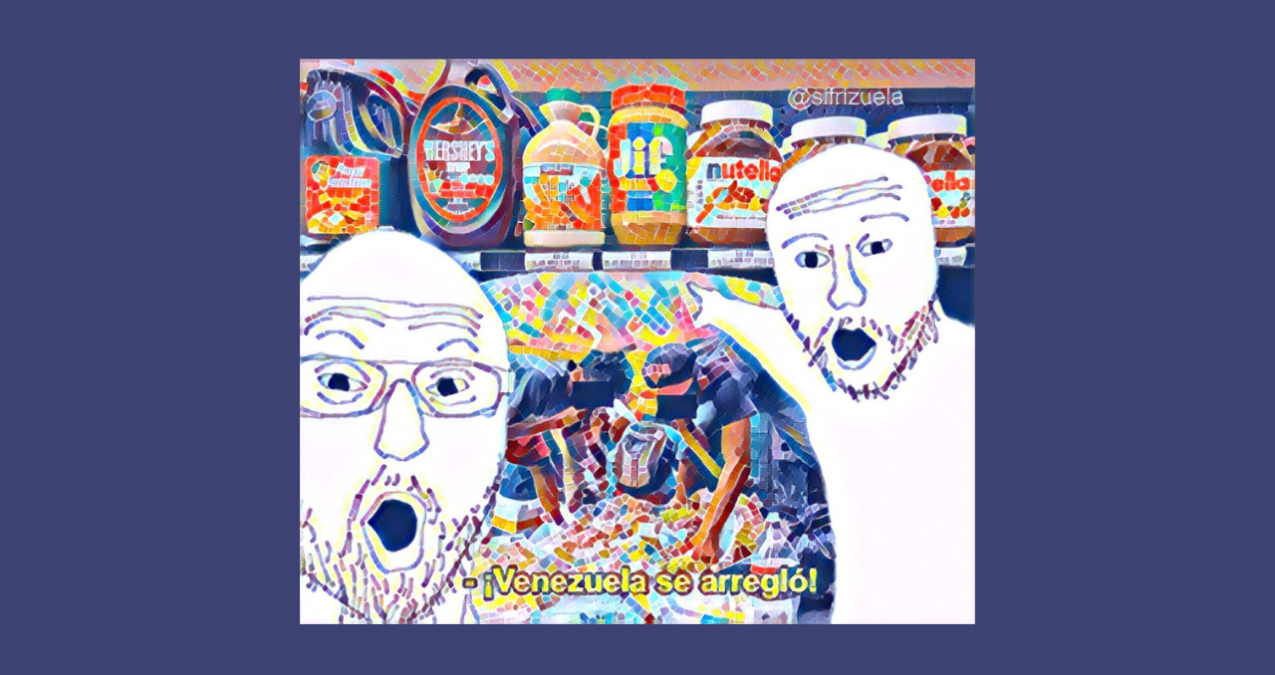

Is someone pushing the narrative of Venezuela’s recovery online? The expression «Venezuela se arregló» went from meme to mantra, and it serves chavismo a little too well

Publicado en: Caracas Chronicles

Por: Tony Frangie Mawad and Pablo Andrés Quintero

After months of rumors pushed by random music accounts on social media, MarketWatch published a press release on April 25th announcing that “Coldplay will perform for the first time in Venezuela.” According to the post, the concert was being produced by Solid Show Productions and it would be held on September 28th at Hacienda Santa Teresa—a touristic estate owned by local rum producer Santa Teresa. The press release even quoted Juan Carlos Araujo, the president of Solid Show. But there was a catch—Araujo was detained in 2015 and sentenced to 20 years in jail for drug dealing and money laundering. Solid Show had been inactive for seven years. Santa Teresa soon debunked the news. Why was MarketWatch—a prestigious financial site owned by Dow Jones & Company—publishing this obvious fabrication?

Truth is, MarketWatch took it from COMTEX, an online distributor of news that picked it up from Vehement Media: an Indian press release distribution service. In fact, the city mentioned for the press release was Coimbatore in Southern India. The media contact was someone named Pranesh Balaji, who works at Amazon Web Services and lives in Coimbatore according to his LinkedIn. Nevertheless, the details on the fake press release were quite Venezuelan: it mentioned TicketMundo and local band Tomates Fritos. Why was a press release distribution company from Coimbatore publishing a press release clearly written by a Venezuelan about a concert in Aragua?

Of course, the possibility of a mere hoax is always there, but one has to wonder if the intentions behind the press release were political—to the tune of the new Madurista mantra, the “economic recovery”. The press release, in fact, mentioned the non-existent concert as “an outstanding event in the history of the country” that would attract concertgoers from nearby countries. Venezuela se arregló!

While the real authors behind the press release are still unknown, the Coldplay fiasco isn’t the only weird internet moment that is seemingly pushing the “Venezuela se arregló” narrative. Weeks before MarketWatch published the press release, a clip appeared online showing three teenage girls interviewed by a reporter in the Morat concert in Caracas. “And Venezuela is getting fixed! Amen!” the first girl said. “Thank you for being light in this moment of darkness,” says the third girl.

Even when the video went viral and was parodied, it never showed the question that the interviewer asked the girls. In fact, the video had been edited to start at the exact moment where one of the girls was saying “…and Venezuela is getting fixed.” And we don’t know how the video jumped from the news in Globovisión—a sanctioned television channel owned by Raúl Gorrin, a powerful businessman close to chavismo who is wanted by the United States—to social media, as Globovisión itself seemingly never published it on its web platforms, and it can’t be found online in its entirety.

Venezuela Is Doing Great—On TikTok

If there’s a “Venezuela se arregló” propaganda campaign online, it didn’t appear in a vacuum. As Luis González explained recently in a superb article, madurismo is pushing a new “good vibes” narrative where Hugo Chávez and chavismo lost the spotlight to an idea of “patriotism for the New Venezuela” that claims there are two sides: a side that wants to see the country progress, the side of growth and recovery, and a side of traitors that wants to see it stagnate and support anti-patriotic sanctions. “This isn’t meant to work on those who have a solid pre-existing notion of Venezuelan culture and values,” writes González, “but for younger generations who grew up under what has been 20 years of chavista governance.”

This narrative of recovery and patriotism has in fact been pushed by accounts and “journalists” that have no explicit ties with the government or state media. For example, self-styled journalist Vanessa Ortiz—who seemingly has no explicit ties with any site or media—published videos on Twitter to show that the country isn’t under an alleged authoritarian regime. “Every weekend, the Maduro ‘regime’ ‘represses’ Venezuelans,” she tweeted with a TikTok video showing SUVs and people partying on a Venezuelan beach.

Ortiz also shared Tiktok videos that show Caracas as a gleaming metropolis, published by José Valero: a TikToker with 52 thousand followers with no explicit ties to state media or the government. Nevertheless, besides his videos highlighting 20th-century buildings as proof of a supposedly prosperous and bright Venezuela or explicitly insisting it is fixed, Valero also published an animated video with a cover of the reggaeton song “Quevedo: Bzrp Music Sessions #52”; a recent hit in Venezuela. The video showing a smiling Nicolás Maduro makes fun of Venezuelan opposition politicians, celebrates inflation in the U.S. and the new pink tide and invites migrants to return to become “entrepreneurs.” The video changes the chorus to “Llégate, que Venezuela está muy bien,” showing restaurants and trips to Canaima and Los Roques while comparing that lifestyle with migrants abroad who “are cleaning for Biden.”

In another video, for example, Valero mentions “a group of ex-Venezuelans abroad determined to lower the self-esteem of Venezuelans in Venezuela.” In fact, such narratives juxtaposing the Venezuelan diaspora with Venezuela’s supposed economic recovery has also been promoted by a mysterious YouTube account called “Retornados Venezuela” which posts well-produced animated videos that make fun of fictional migrations being exploited abroad while their friends in Venezuela go to concerts and boat parties. The message is clear: Venezuela is fixed, with restaurants and music concerts, and migrants who believed in the opposition’s “lies” and are now cleaning toilets abroad should return to the motherland.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=sh-h4Pisz70

Retornados Venezuela isn’t the only mysterious YouTube account: an account named “Venezuela se arregló” that shows Friends episodes edited to include chavista officials as its characters, bashing on the opposition and its failures. With paid ads, its videos have almost reached 130,000 views. And throughout TikTok, showing luxurious hotels in Mochima or race cars and Rolex watches in Caracas, low-profile content creators post under the Venezuela Premium banner.

Changes in narrative like this are stimulated with careful consideration and planning. Political conditioning requires an understanding of the psychological state of mind of the population including its frustrations, fears, hopes and perceptions of power. And the new local economy of bodegones, concerts, department stores and dozens of new restaurants every month contributes and supports the idea of this new image of well-being.

In a context of a systematic censorship of both traditional and digital media, it isn’t relevant how credible or sustainable this is, what matters is that the idea of a Venezuela arreglada, a fixed Venezuela, has been implanted and is discussed by media content producers: the result of the beginning of the pandemic in 2020 marking a new strategy focused on the digital world. As the quarantine increased the use of social media and the population identified with and shared the positive and fun messages they received, the regime adjusted its own message to this new emotional climate. The contrast with the opposition’s gloomy narrative was stark.

Madurista Aesthetics

Exploiting its new “good vibes” narrative, the regime has put “happiness” as the core of its communications and it will be the spearhead for the upcoming elections. The opposition’s “Vamos bien” has been appropriated by the regime and it now reads “Venezuela se arregló.” Throughout cities, Misión Venezuela Bella—with its heart-shaped logo—is reminding citizens Venezuelans that “together, everything is possible” in multicolored letters. Christmas decorations are now set in October, towers in Caracas are being refurbished with facades of colorful lights and Plaza Venezuela and Los Próceres are decorated with flag hearts.

The construction of a new image for maduristas, although rejected by dogmatists and nostalgic chavistas, is also part of the new communicational strategy of the governing elite. This new image wears suits and dyes its hair blond: almost as if trying to look like the once-despised sifrinos. It’s not just a new dress code, but a new nonverbal message which includes a supposed ideological moderation and a sense of partaking in the happiness of the new times.

In fact, part of the new communication is focused on diluting the most dogmatic and aggressive propagandistic elements of chavismo: those values that represent an archaic socialist and praetorian model and its state surveillance. Chavista candidates avoid the color red in electoral ads and the posters of Chávez’s Orwellian eyes have been replaced by advertising. No one wants to be surveilled, especially by eyes that are now a part of the past.

A change of aesthetics and the appropriation of cultural elements of the opposition are not limited to politicians. In the last two years, the “Humboldt Hotel model” of rehabilitating pre-existing city structures to showcase economic recovery and spectacular progress has been pushed to transform Caracas into madurismo’s model city. For example, by covering it with new sculptures of Indigenous figures and palm-ridden gardens next to the highways, by removing Chávez’s image from billboards and murals or by installing LED and multicolored lights in tunnels or public squares. In fact, the Teresa Carreño Theater and the Museum of Contemporary Art—two icons of Venezuelan democracy, politized or even renamed during Chávez’s years—have been renovated. The Teresa Carreño Theater even has a new management that has returned to an old-school non-political agenda and now works with the private sector to finance musical plays and ballet.

Chavismo Chévere

One of the electoral objectives attached to this new branding is to conquer the spaces and sympathies of the Venezuelan middle class without any toxic political conversation. The current economic recovery requires a certain harmony and political consensus with the business class and the sedation of the most anti-chavista demographic. It’s a convenient approach that can avoid uncomfortable encounters and is focused only on transactions and benefits. “Let’s do business without talking politics” is part of the new dynamic of multicolored inclusion and strong pragmatism. The new digital and physical propaganda has opened a new dimension of vast political pragmatism that has understood the necessity to create a new electorate that is more useful and attractive.

Of course, the communicational reality of the people that live outside of Caracas is completely different. They are less connected and the daily activities of many are linked to survival. They don’t have the time or interest to process politics. The “Venezuela que se arregló” hasn’t reached them. Memories of the days in which mangoes and bitter cassava were used to satiate hunger and people traveling in “perreras” (load trucks used to transport people), seem distant. Yet, structural poverty and inequities remain the same but they are not showcased in Caracas—where 37.6% of rich households are concentrated according to Encovi and which represents 40% of the GDP, according to Ecoanalítica.

Thus, as the 2021 regional elections showed, the highest voting rates are found in rural regions that were once strongholds of chavismo: the opposition won the governorships in Chávez-birthstate Barinas and in Cojedes, which also had the highest participation rate in the country. It also won dozens of municipalities in other rural states and almost won the governorship of Apure. Meanwhile, the opposition’s strongholds in eastern Caracas showed some of the highest abstention rates: its core has become apolitical and skeptical.

“Venezuela se arregló” aims to change the emotions associated with past and current events, winning NiNis (voters that are neither opposition nor chavistas), while also taming a historically antichavista middle class, especially its youth. Although facts remain, their interpretation and the emotions they elicit can be manipulated; especially after the 2019 national blackout gave the regime a chance to cool down protests and to refocus on four strategies: offensive actions, dissuasion, justification, and dispersion.

Now, madurismo is seeking to “delete” the emotions associated with times of suffering, negligence and abuse: according to polls by More Consulting, those who perceive Maduro’s management as negative may have decreased from 80,4% in May 2017 to 60,9% in May 2022. Heading towards a new national election, the regime is introducing new conversations and emotions that are able to move people. It needs to create the illusion of happiness and make the voters believe they will have access to it. And it may be working.